In May this year, The New York Times columnist Peter Coy published two consecutive articles ( Why Can’t College Grads Find Jobs? Here Are Some Theories — and Fixes. and Highly Educated Grads Can’t Find Work. What’s Happening?), focusing on the employment difficulties faced by American college graduates.

Peter Coy received numerous heartbreaking stories when collecting job-hunting experiences from graduates: unanswered applications, lowered expectations, and some even pessimistically saying that attending college felt like a waste of time and money.

In one interview, John York, a student about to receive his master’s degree in mathematics from New York University, who holds a patent and has passed the Chartered Financial Analyst exam, reported submitting nearly 400 applications and receiving fewer than 40 responses, all rejections. He speculated that he couldn’t find a job because there were no entry-level positions available. He described the experience as “a deafening silence, each application feeling like shouting into the void.”

Another student, Mauricio Naranjo, was looking for a job as a graphic designer. Over the past year, he submitted more than 400 applications, mostly receiving responses that appeared to be generated by artificial intelligence: “Unfortunately, we have chosen another candidate who better meets our expectations.” Even these replies were rare; most did not respond at all.

Beth Donnelly, fluent in three languages, has been looking for full-time, part-time, or internship positions since last August. She had to gradually lower her “expected salary” to $35,000 a year, hoping someone would think, “Oh, I don’t have to pay this person as much, so they have an edge in the hiring process.”

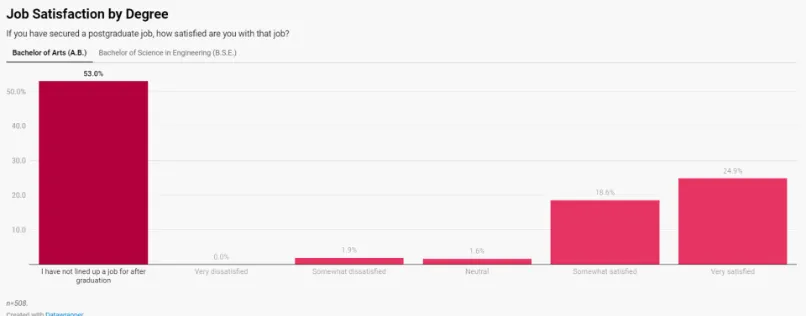

According to the Princeton University website:

- Over half (53%) of humanities undergraduates have not found jobs.

- The employment situation for STEM graduates is slightly better, with only 25.4% unemployed, but 28.9% of students are dissatisfied with their jobs.

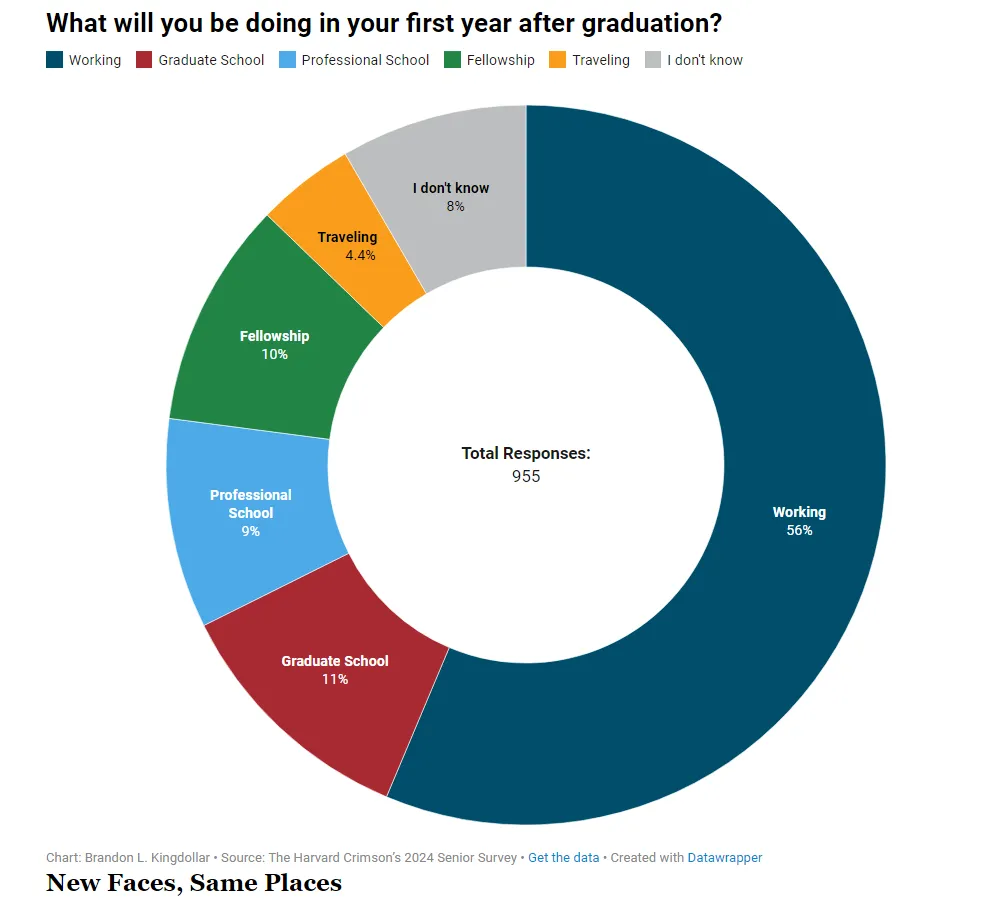

A survey of 955 current graduates from Harvard University showed that less than 60% chose to seek employment. If job prospects were ideal, not so few graduates would choose to enter the workforce.

Data from The Harvard Crimson

Matt Sigelman, a visiting scholar at Harvard Kennedy School, stated four months ago that even in a booming job market, 52% of graduates found jobs that did not require a college degree. Worse, few of those who started underemployed could find jobs requiring their degrees, leading to an annual income $20,000 less than their peers, a gap that would persist throughout their careers.

The situation is not optimistic in Canada either: Jenna Benchetrit mentioned in a CBC News article that Surya Nareshan, a graduate in engineering physics from Carleton University, applied for over 80 positions since graduating in May 2023, but only received a few interviews. He said, “I’ve applied for over 80 jobs but often get no response.” RBC Economics’ analysis shows that much of the increase in Canada’s overall unemployment rate since last April is due to new job seekers—young people and recent graduates like Nareshan—spending more time job-hunting. The data shows that employment for 15 to 24-year-olds has seen almost no growth since December 2022.

Furthermore, Benchetrit’s CBC News article noted that among students returning to school, the employment rate in June 2024 was 46.8%, the lowest since 1998, excluding the first year of the pandemic in 2020. The data also indicates that students face more difficulties in the summer job market, especially in the restaurant and hotel industries.

Looking at this year as a whole, it seems that global university graduates are collectively cursed, unable to find jobs.

They could be considered the most desperate generation, evoking both sadness and sympathy.

However, data released by the U.S. Department of Labor at the beginning of June showed a national unemployment rate of around 4%, with 272,000 new jobs added in May, indicating that the labor market remains relatively strong. Average hourly earnings in May increased by 4.1% year-on-year, both figures exceeding previous expectations. On the other hand, Canadian statistics show that the employment rate for young people has gradually rebounded since hitting a historic low in May 2022, but the current market remains challenging for new graduates.

All data confirm that the labor market is recovering.

But why do so many graduates still struggle to find employment? Media and experts analyze several reasons:

1, Mismatch between job shortages and graduates’ goals.

The job market does have some shortages, but mainly in low-skill positions such as construction, services, farms, restaurants, daycare centers, nursing homes, administration, and customer support—sectors that are clearly not the target industries for university graduates.

2, Fewer available job positions

Despite the low unemployment rate, the quitting rate is also decreasing, reducing the number of available job positions. LinkedIn estimates that the national hiring rate in April fell by 9.5% compared to the same period last year.

3, Favored Industries experience lay-offs

Industries favored by university students—technology, finance, consulting, and media—have been continuously laying off employees and reducing hiring plans in the past two years.

According to Layoffs.fyi, a company that tracks global tech company layoffs, 293 tech companies worldwide laid off a total of 84,060 people in the first four months of this year. In California’s San Francisco Bay Area, the tech industry has laid off 19,533 people since the beginning of this year, with the most layoffs from Cisco (4,250), VMware (2,837), PayPal (2,500), Unity (1,800), and Google (1,257). Tesla President Elon Musk announced in April that at least 10% (14,000) layoffs, but due to a 20% decline in vehicle deliveries from the fourth quarter last year to the first quarter this year, insiders analyze that the actual layoffs may exceed 20,000.

Throughout 2023, 262,600 people left the global tech industry, far exceeding the 164,900 people in 2022. The companies with the most layoffs were Amazon (27,000), Meta (21,000), Google (12,000), and Microsoft (11,000). Other U.S. tech companies that laid off large numbers of employees post-pandemic include SAP America and Apple.

On Wall Street, amid the “deal drought,” the six largest banks—Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo—cut about 21,000 jobs in the first half of last year. The winter continues.

Other popular industries are facing similar situations.

4, Preferring to hire experienced employees

Employers expect graduates to immediately create tangible value, preferring to hire experienced employees, being more distrustful, cautious, and demanding of recent graduates.

Experts from Goldman Sachs’ economic team suggest several potential reasons, including that the 2024 graduates experienced remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have affected their training, interpersonal networks, and accumulation of human and social capital.

Work experience during university is crucial for landing the first job, creating a paradox of “needing work experience to find a job.” The phenomenon of “spending all four years of university job-hunting” and “university solely to obtain a job” has become regrettably common.

5, Harder to stand out

Too many job seekers make it harder to stand out and be noticed. Personal connections are crucial.

Simply submitting resumes and cover letters to company job portals has a low success rate, especially now. Applications have become so easy to submit that they get flooded with thousands of applications. Humans can’t review all applications, and computer screening only searches for keywords without deeply understanding the applicant’s qualities or employer’s needs.

“The better you write, the more likely you are to be rejected because you won’t use the keywords the hiring algorithm wants,” said Nick Corcodilos, a recruiter who runs the website Ask the Headhunter. He suggests not sending broad applications but focusing on a few companies, researching them deeply, and connecting with various people related to them, including their suppliers and customers.

Forbes conducted a survey in April this year on employers’ views on hiring talent. Recruitment managers were asked about their opinions on public university graduates and non-Ivy private university graduates:

According to the April Forbes survey, 42% of hiring managers with direct hiring authority now prefer hiring public university graduates; 37% prefer hiring non-Ivy private university graduates, an increase from five years ago; only 7% said they are more willing to hire Ivy League graduates than before. Employers increasingly prefer recruiting top-performing professionals from other institutions, which Forbes calls the “new Ivies.” Only 14% praised Ivy League schools similarly, while 20% said Ivy League schools’ performance had worsened, making it the only category with a negative trend exceeding the positive.

Prospects are many people’s guiding stars and indicators. Under these circumstances, how long will the track of prestigious schools and popular majors, favored by parents, remain appealing?

Should we reflect on the essence of university education and return to focusing on the individual, making different choices?